Well before SoundCloud, MixCloud, MixCrate, Podomatic, TheFuture.fm, Play.fm and others (I’m sure are out there, but I’m not yet familiar with) inherited their spots as the most popular services where DJs can upload their DJ mixes then share them in social media, or have them pulled up in smart phone apps for on-demand listening over mobile, there were earlier attempts at bringing the DJ mix online.

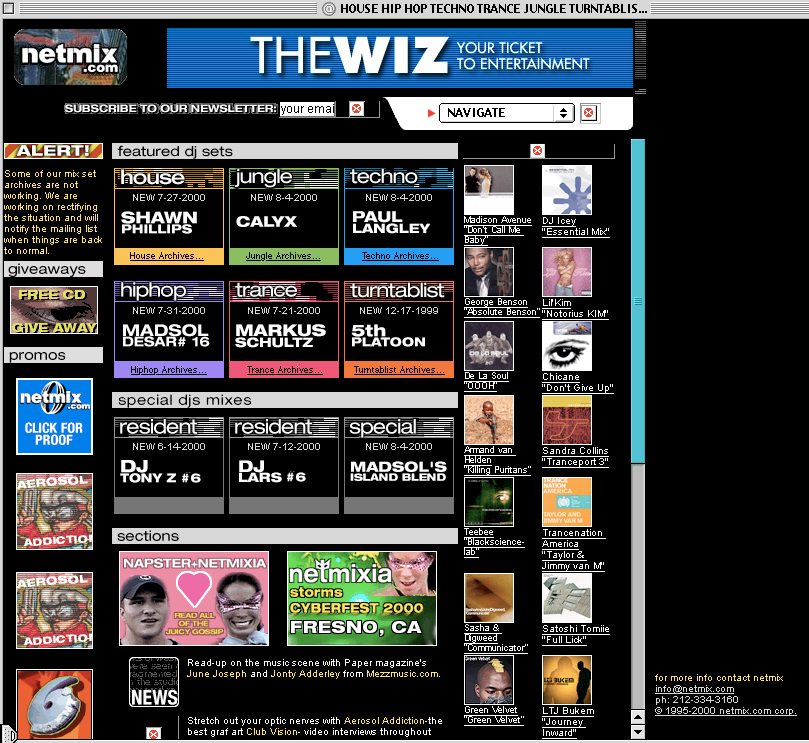

In December of 2015, some 19-years ago, I registered this domain, Netmix.com, and launched the first organized DJ mixshow website in the world. Many of the DJ sets I encoded, uploaded and streamed in Real Audio 1.0, where from the world’s most sought after DJ/Producers at the time, including Armand Van Helden, Paul Oakenfold, Lil Louie Vega, Tony Humphries, Frankie Knuckles, Jody Wisternoff, Frankie Bones, Richard “Humpty” Vission” and the list goes on.

Shortly after I launched Netmix, other services began popping up, including Swedish Egil’s Groove Radio in Santa Monica (which had already been broad, CA; GrooveTech from Seattle; The Womb in Miami; and the folks at Streetsound Magazine in NYC, a subsidiary of legendary pre-1.0 bubble Pseudo Networks, which released DJ mixes as streamed live video sets. That was well before today’s UGC (user-generated content) services like LiveStream and Ustream were born.

In the early days of the Internet, there were few rules. The Digital Millenium Copyright Act of 1998 had yet to be passed into law. Streaming music online was certainly a Wild West. You could get away with just about anything – as long as you kept things under the radar. In this pre-Napster era, web servers and bandwidth weren’t powerful enough to stream MP3 over HTTP, let alone allow people to download them. If you were in the streaming game, you had to either buy or lease space on a Windows Media, Real Audio or Apple streaming server. Real Audio being the most popular, albeit the more expensive of the three.

Labels were experimenting with music promotion online and Netmix was part of those early online marketing efforts, making some of its revenue by building artist landing pages on Netmix (like shown in the home page image below). We’d send feedback to each label on unique visits to each single or album. We were responsible for some of the first Internet marketing efforts on behalf of dance/electronic artists for Sony Music, Atlantic Records, Roadrunner Records, Profile Records, Tommy Boy Records and Arista Records, as well as a number of smaller independent dance labels. We’d also started managing DJ producers and commissioning remixes. We signed records to Defected UK and Perfecto UK for artists on the Netmix roster.

When the Digital Millenium Copyright Act was finally passed and the later Small Webcasters Settlement Act of 2002 came into play, webcasters like Netmix were required to pay ASCAP and BMI a percentage of income, so they could pay out artist royalties for the public performance of the music in the mix shows. Given the costs at the time of streaming and bandwidth, it became less profitable for a webcaster like Netmix, without the backing of a major company, to survive on mix shows alone. There’s a lot more to it, but for the purposes of this post, that should suffice.

In June of 2000, Netmix because the third (after Streetsound and Groove Radio) to be acquired by a larger concern, yet left to run our Internet broadcast outlets under our brand names. By October of 2000, our parent company folded under the weight of the dotcom 1.0 and couldn’t raise any more money for operations. The company’s staff was laid off and Netmix went out on its own, but struggled to survive when labels were cutting budgets and the economy had tanked.

For the 5-years Netmix was running full-steam, our mixes were primarily broadcast as non-interactive streams. When I relaunched the site as a blog in the 2004, for a short time we paid for live streaming services using Live365.com, because they had figured out a way to allow broadcasters to stream archived shows as live webcasts, while factoring part of the subscription fee and pre and midstream advertising as payments to the performing rights organizations.Live365 was one of the first companies to advance this type of arrangement and others soon followed. This was legal and generally fit the requirements of the DMCA. These are the rules as published here by Live365 today:

DMCA Rules

The following is a partial list of the rules with which Live365’s Internet broadcasters must comply under portions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. ß 114, given the nature of the licenses Live365 has obtained from the owners of the copyrights in sound recordings. Please note these licenses only cover personal broadcasters and do not necessarily cover PRO broadcasters on Live365. We have abbreviated these rules to include only those that likely would be relevant given the manner in which you are able to use the Live365 system. The relevant rules which you must carefully review are as follows:

-

Your program must not be part of an “interactive service.” For your purposes, this means that you cannot perform sound recordings within one hour of a request by a listener or at a time designated by the listener.

-

In any three-hour period, you should not intentionally program more than three songs (and not more than two songs in a row) from the same recording; you should not intentionally program more than four songs (and not more than three songs in a row) from the same recording artist or anthology/box set.

-

Continuous looped programs may not be less than three hours long.

-

Rebroadcasts of programs may be performed at scheduled times as follows: Programs of less than one-hour: no more than three times in a two-week period; Programs longer than one hour: no more than four times in any two-week period.

-

You should not publish advance program guides or use other means to pre-announce when particular sound recordings will be played.

-

You should only broadcast sound recordings that are authorized for performance in the United States.

-

You should pass through (and not disable or remove) identification or technological protection information included in the sound recording (if any).

As you can see, the published rules above are very restrictive and that is for a reason. During the DMCA negotiations, the labels were very concerned about things like playing an entire album by one artist or looping the same shows excessively. They fought to prevent Internet broadcasters from pre-announcing track names, which can only be published in a player during playback and never before. In the world of DJ mixes, one company, Digitally Imported Radio (di.fm) stands out, because the station adheres to the DMCA and broadcasts online non-interactive streams. While it is most likely operates under a compulsory license with ASCAP, BMI and SESAC to pay songwriters their performance royalties, it also has a direct deal with SoundExchange to pay the artists themselves royalties as well.

SoundExchange is an entity created by the government to collect payments from Internet broadcasters for non-interactive Internet broadcasts of music that is then paid to the artists themselves, unlike terrestrial radio, which has not had this requirement, but may be forced to do so in the future as hearings are taking place now with the Senate Judiciary Committee. This may result in a change to the law.

Di.fm stands in stark contrast with all the services listed at the beginning of this article, because all of those services allow for upload of user-generated content and playback as an on-demand stream, which is interactive by nature. What’s the difference? According to the DMCA, an on-demand interactive broadcast requires a mechanical license from the copyright owner. Spotify, Apple’s iTunes Radio and Beats Music services pay tens of millions of dollars in advances to record labels to get rights to play music on-demand – that is, when the listener requests to play it at that moment.

Services like Pandora and 8tracks (disclosure: I am an adviser to 8tracks) do not fall in this category as they are strictly non-interactive and adhere to the terms in the DMCA. However, all the above mentioned services at the beginning of this article have not negotiated similar deals with the labels in regards to on-demand streams. At a New York Technology and Music Meetup a few months back, Nico Perez from MixCloud claimed that their attorney (who he said was also Pandora’s attorney) says they are operating under a specific clause of 17 U.S. Code Section 114 (b), which talks about a derivative work.

(b) The exclusive right of the owner of copyright in a sound recording under clause (1) of section 106 is limited to the right to duplicate the sound recording in the form of phonorecords or copies that directly or indirectly recapture the actual sounds fixed in the recording. The exclusive right of the owner of copyright in a sound recording under clause (2) of section 106 is limited to the right to prepare a derivative work in which the actual sounds fixed in the sound recording are rearranged, remixed, or otherwise altered in sequence or quality. The exclusive rights of the owner of copyright in a sound recording under clauses (1) and (2) of section 106 do not extend to the making or duplication of another sound recording that consists entirely of an independent fixation of other sounds, even though such sounds imitate or simulate those in the copyrighted sound recording. The exclusive rights of the owner of copyright in a sound recording under clauses (1), (2), and (3) of section 106 do not apply to sound recordings included in educational television and radio programs (as defined in section 397 of title 47) distributed or transmitted by or through public broadcasting entities (as defined by section 118 (f)): Provided, That copies or phonorecords of said programs are not commercially distributed by or through public broadcasting entities to the general public.

This clause protects fair use of musical works as a derivative work for a variety of reasons, including political or artistic. This is the same clause cited by mashup producers who know they cannot sell their work, so they give away their mash ups to increase their profile resulting in paid gigs to perform the mashups as artist or DJ in a live performance. As long as they don’t sell or monetize their mash ups, these mash up producers are protected by Section 114 (b) . But, for MixCloud to claim that DJ mixes are akin to mash ups is a stretch of the imagination, because often times, while a segment of a DJ mix may be a new composition rendered when the next song in a playlist is cued and beat matched over the previous song, the following minutes of playback of the new song surely cannot be considered a mashup. There is nothing unique about that excerpt, except for maybe the pitch was adjusted and the song is a little faster or slower than originally intended.

Shortly after that episode, MixCloud changed their terms and conditions and we are now hearing reports from DJs uploading new content that MixCloud is issuing takedowns of mixes they may consider infringing. This follows SoundCloud’s lead, which I previously wrote about here. I am not writing this because I hold any grudges against MixCloud for succeeding where Netmix was, well…not so successful over the long term, despite its pioneering status. I’m proud of that team for building a unique service and getting it to this level. It’s a great service and I even use it to publish my Netmix Global House Sessions Podcast. They’ve done an excellent job, but at the end of the day, what they are doing still does not adhere to the letter of the law.

Remember, MixCloud is fully interactive. In the mobile app, you can start a mix show on demand and skip through the full mix. This requires a mechanical license for each song in the DJ mix. There is no blanket compulsory license that covers this and until there is one, MixCloud is skirting the requirements of the DMCA. And, this is the very reason I don’t get into this business, because the DJ mix simply cannot be controlled by the DMCA, but if you start a music service based on the DJ mix, you’re surely going to run into this issue – time and time again. It’s not worth it. That document doesn’t take into consideration the value of a DJ mix to the artists and labels how use them as promotional vehicles. Until the DMCA is updated or some new compulsory license for an interactive performance comes into play, then all mixes that are interactive are simply not legal. Podcasts are another story and those have to be licensed as well.

That bring us to our last issue with TheFuture.fm, a service that claims it pays all artists royalties for songs played in DJ mixes. First, it’s impossible to accurately pay artists anything without exact meta data. How TheFuture.fm can be absolutely sure that every DJ mix uploaded has the exact per track meta data is beyond me, because that is simply not possible – unless, of course, a human being opens every MP3 used by the DJ in the mix and checks the ID3 tag to ensure the meta data is accurate.

Second, even if TheFuture.fm pays artists royalties through a compulsory license, that’s still circumventing the mechanical license needed for every song that is included in an on-demand, interactive stream. I checked some of the mixes today and yes, they are on-demand and interactive – I can skip through the mix. As I said before, there is no compulsory license for on-demand interactive streaming and it would cost tens of millions of dollars to pay to the entire recorded music industry to allow for this. Even then, what is played is sometimes not known and if it is known, then the meta data may not be accurate anyway.

The funny thing about many of these services is that they start over in London and for a reason that I can’t yet figure out, they are allowed to thrive, even though some of the same rules apply there. They attempt to cross the pond and break into America, where they are absolutely 100% aware of the DMCA restrictions, yet somehow they raise money and try to circumvent the rules (ala Uber or AirBnB), only to have to capitulate as SoundCloud has done and MixCloud is now starting to do.

One of the other services I mentioned, Play.fm, happily operates in Austria and has cast no aspersions on entering the U.S. market in the same way. When I first met the Play.fm team at a Winter Music Conferece in the mid-2000s, I learned they get funding from the Austrian government, so they wouldn’t be able to get seed funding from investors in the U.S. anyway, because they’re not set up like more traditional start-ups who are self-funded or investor funded. I also believe Austria is not as restrictive regarding streaming rights and licensing (but I could be wrong.)

At the end of the day, I want to see these service thrive and survive. I love DJ culture. It’s in my blood. I’ve been involved in the scene for over 30-years. Plus, I want to be in the game and I want my DJ mixes on these services. However, there is a reason that Netmix is a blog today and not a DJ mix service (although I do host my mixes as podcasts that remain unlicensed). Those reasons are clear – the DJ mix should be an on demand format. For that to happen, DJs need a compulsory license for the mechanical, which does not exist. Until that exists, we are all operating in the grey area and not one of us can bring a DJ oriented music service to market that is innovative and allows interactive, on-demand performances, until the rules change.

That means, until that happens, I’m sitting it out. I’m not going to waste investors time and money running up against the music industry, which will sue me out of existence or have artists and labels issuing takedowns and ruining the service’s reputation while frustrating users. Should artists and labels fight back? Yes. As long as these are the rules, they have every right to issue takedowns and make life hell for all the DJs out there. Now that DJs are getting paid big money in Vegas or these huge festivals to spin, some artists are saying they want a piece of that pie too. But, those artists have to remember that the festivals and clubs are licensed by the PROs, so they are still getting paid when their music is played. A few things that would go a long way toward helping artists get the money they deserve would be technology that accurately tracked the public performance of DJ sets in live environments and the adoption of ISRC by DJs attached to their mixes. But, those are articles for another day!